Well, this is going to be a popular post, huh? The idea that you should love airline fees probably sounds ridiculous to you. After all, complaining about fees has now replaced complaining about airline food as the traveler’s favorite pastime. But you really should be happy that there are fees out there. Before you start an internet campaign to talk about how much I suck, hear me out.

Since airlines are private entities, I assume we can all agree that airlines have a right to make a profit. If airlines were run by the government, then that would be a different story, but they aren’t. So airlines are trying to make a profit (some better than others) and should do whatever they can to get to that point. On a basic level, this means revenues need to be higher than costs. Ok, I think we’re still on the same page.

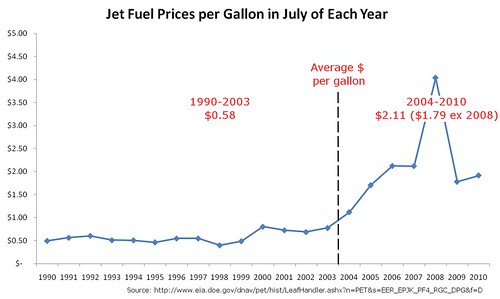

The problem, of course, is costs have spiked to a new sustained high level in the last few years thanks to jet fuel prices. This is probably familiar to many of you, but take a look at this graph showing jet fuel prices per gallon at the beginning of July in each year:

Even excluding that spike year of 2008, jet fuel prices have still more than tripled to become the largest single cost at many airlines. And fuel prices is pushing higher once again as I write this. Just think about that. Let me try to put it in easy-to-relate terms.

Let’s say that you sell televisions and times are good. To make this easy, you only sell one type of TV and it sells for $550. Your total costs average out to $500 a TV, so you make a 10 percent profit. (That’s not great for a lot of businesses but for airlines it would be stellar.) Up until now, your cost for a screen has consistently been $50, or 10 percent of your total costs. But all of a sudden, there’s a change in the screen world and prices permanently jump by 300 percent. Now, screens cost $150 and there’s absolutely nothing you can do about it. If you keep prices where they are, you lose $100 per TV for a negative 18 percent margin that will put you out of business.

So you have to raise prices to cover your costs. You think about jacking up prices from $550 to $650. You’d make a 7.5 percent margin which is ok but a lot fewer people want TVs at $650 than they did at $550. This is where things get ugly.

If you bring prices up to $650, you have to figure out how many TVs to make. After doing the math, you realize that if you jack up prices to that level you might lose half your demand. Since you have so much invested in the factory and tooling, if you cut your production by half, the cost per TV will rise dramatically because you have fewer TVs over which you can spread your fixed costs. It might rise to, say, $700. Then you’d have to raise prices even more and that’s going to cut demand even further. It’s an ugly spiral.

There are a couple ways out of this. If you’re a manufacturer of TV, you can just keep producing TVs and sit on them until you hope demand grows again. But that’s not an option for airlines, so let’s pretend that’s not an option here. So that cuts down on decent options dramatically.

You can lay people off, but you also need to get rid of machinery and tooling that you don’t need anymore. You might need to move into a smaller factory too. This might not even be possible so you have to consider bankruptcy to keep your company as a viable ongoing operation. There has to be a better way.

You then realize that there’s a way to keep prices in check without killing demand. You do raise your prices about 10 percent to $599 and most people are still willing to pay that much. But now, you tell people that the $599 version doesn’t have HD capability turned on. To get that, they’ll have to pay an additional $25. Then you start adding new options to help get the price up. They can order a deluxe remote control for $25. You start offering wifi capability for another $25. Now, those people who want the add-ons can pay more for them. But those people who wouldn’t pay the higher price can still get a base unit for a relatively affordable price. People can buy what they want and demand stays relatively high.

In the end, your total revenue per TV goes up to $700 with all of the add-ons that people choose. The basic TV being priced at $599 still keeps demand high for the unit, but the amount that some people pay to dress up their TV to make it better is what actually pushes you into profitability.

This isn’t a perfect comparison, of course, but the idea is sound. With the high cost of fuel today, there are two ways the airline industry could go. It could keep the previous pricing scheme but that would mean a lot fewer flights, much higher fares, and probably another visit to bankruptcy-land. Or it can provide a menu of options via fees that keeps the base price low for the no-frills traveler and still keeps a broader schedule available to serve everyone.

In the end, fees are a good thing. I may not like how many airlines have implemented them in a clunky, difficult to compare way, but that will change as airlines start to get better at this and consumers demand more. It doesn’t change the fact that the a la carte pricing method is a good thing for this industry.